My daughter started a blog for me. I am an entrepreneur with over 40 years of experience developing indigenous designs for specialized robots and embedded systems in India. I have two children, to whom I have successfully passed on my love for science and engineering. My wife has patiently listened to me talk about technology, economics and India for over 40 years, while she has gone about educating and inspiring young minds in the field of computer science, robotics and design. As I contemplate the next phase of my life, and the India that my grandchildren will inherit, my daughter asked me to start a blog to share my musings. This is it.

How much Big Data is sufficient?

Data reveals insight. Historically, the Census conducted every 10 years reveals information about education levels, income levels, number of school going children, number of people employed, number of dependents etc. From all this data, the government can frame policies, directed at segments of interest. Similarly, market surveys conducted by consumer research organisations reveal information about product preferences, critical price points etc.

Today, with the generation of data from mobile phones, instant messaging systems, emails, websites, IOT devices, the volume is huge. Tech giants are using this data, and a mix of good old statistics, coupled with neural networks running on specialised hardware, to brew the magic of AI.

AI is everywhere, but this blog is not about AI per se. The question is “Is there a minimum amount of Big Data that can do the job?” or , is it true that “the more the size of big data, the more powerful the AI would be?”

This is not a trivial question, and it is already “hurting the big guys”. Google has started informing users about exceeding the free 15 GB storage limit. Whatsapp has introduced Disappearing Messages. Facebook has permitted posts with a timer limit. Is there a pattern here?

If one were to read all the emails of a particular person, obtain data about every transaction she makes, read all her messages on various messaging platforms, every picture she posts, every place she visits, dines or shops, note every message that she likes, does not like, or ignores:

- How long would it take to create a profile of the person regarding her place of residence, taste, her work, her socio economic status, her preferences in life, her network, her political and social views?

- As time passes by, and more and more data is created, is there a point where the algorithm would be learning incrementally less each time, when another big chunk of data came along? Is there a point of diminshing returns?

I believe, the answer is a BIG YES.

The early bits of information about any person reveal a huge amount of information (read insight). As more and pieces of data start coming in, a pattern starts developing, where fresh data does not give any further insight than what was already known.

Most of the readers would agree with me upto this point. The next big question is “How much is enough?”

This blog is only about determining whether a size limit exists.

It also begs the question, that an efficient profile building algorithm, would be able to “know a target” with very small amounts of data, which is processed as it is generated, refining the profile continuously with every input, and finding that beyond a certain point, fresh data does not change the model coefficients significantly. In other words, at this point the algorithm knows practically all that is required to be known.

While one has focused on an individual subject, aggregation of such subjects will similarly yield information about the residents of a town, a city, a state or a country, with the principle being the same.

Is there a clue in this blog, as to how the next generation of AI systems will be built? I would like to hear your views.

In defense of Passive Surveillance…?

They changed the world for good, and then became monsters. You love them, you hate them. Some would not live without them, others would prefer to live without them.

The Internet is now synonymous with Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and their ilk. It is the place where people sell and buy stuff, avail of services and do things good and bad.

All the big companies which dominate the Internet are accused and considered guilty of using data. Data is the new gold, it is said. However, I would like to pause and reflect.

Are the IT giants bad guys? The opinion is divided. Is the market place on the Internet different from the market places of earlier years? Yes and No.

All operators in the market place need market intelligence. The buyer needs to know where to get the stuff he wants at the best price, and the seller needs to know if a particular person would be susceptible to make a purchase or may be induced to make one.

How does all this happen? The answer quite simply is “intelligence” which is based on “data” generated through “surveillance”. Why do these words sound ominous to the lay person? People are known to say “That’s a lovely dress, where did you buy it from?”. The reply could be a particular store in a particular location, or it could be “Myntra” an online store.

So what is the difference between then and now. The only difference is the use of interconnected computers, which store all this information, to be served to the user who demands to know. There is not much difference between the yellow pages of the earlier years, and the search on Google or Amazon.

Really? The answer is once again Yes and No. Yes because from the point of view of the seller, there is not much of a difference; but from the point of view of the buyer, there is. The difference lies in that earlier sellers wanted their wares to be known to the buyer, and today it is possible to determine which buyer would be willing or wanting to buy what?

So, why is this difference so important? What is this obsession with privacy? Would it not be nice, if you were to go to a building housing many services, for a service provider to know that you have come for a hair cut or to buy batteries? This is only possible if somehow a method could determine your purpose of your visit.

If a person looks at a dress in a showroom’s window, longer than a passing glance, an astute salesperson would not take long to determine the prospective buyer’s interest. What is wrong in the salesperson approaching the person, and helping her in making a decision? Has the salesperson violated the prospective buyer’s privacy by reading her mind?

It is different, others would argue, choosing the line, that when a machine does it, or an algorithm determines it, then that artificial thing is “spying” on you. There is an extended fear that if a “machine” could be spying on you, it could know your deepest secrets.

The fear is not unfounded. Yet, we have little problem in keeping the mobile phone by our bedside, without even realising that some “app” could be listening to everything we utter. And why just the bedside? The mobile phone is always with us – in the restaurant, in the meeting room, in the lecture hall? How do we know that someone is not eavesdropping all the time.

When Microsoft bought Hotmail from Sabeer Bhatia, and provided the mail service for free, only to be joined by Yahoo, and Gmail who provided the same service, how many of us gave it a thought that the machines would be reading the mails. Today, when the usage is rampant, and the service providers admit it openly, why has it become such a big issue?

Is the world a better place? Are we moving in the right direction? Do we need a course correction?

from Computer Science to Law

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a scientist. My dream was to have my own library of books and have a lab where I could do my experiments. I achieved this dream, not wholly but in substantial measure. In PRAVAK, I had a large volume of books, including eBooks, and space to tinker and make new machines.

Once I started running a company, I realized how difficult it is for an entrepreneur to run a business. As I encountered law after law, rules after rules, I realized that something that is supposed to act as a facilitator can also become an impediment; I was busy running a company and raising my family and took these as normal hurdles in business.

Once, we had to import DC motors. The Customs Officer said I had to pay a duty of 160%. I checked up the tariff tables and sure enough, DC motors attracted 160% duty, and hey wait, DC generators could be imported by paying only 60% duty. As an engineer, it struck me as very odd. A DC generator and a DC motor are the same thing. In a motor, you put in electricity at the terminals and the shaft rotates. In a generator, you rotate the shaft, and it generates power. I tried to convince the commissioner that they were the same thing, and hence two different duty rates were not proper. But no, he was not convinced. I was annoyed and compelled to pay the higher duty. However, I told him that the next time, I import this item, I will import it as a DC generator. He scoffed at the idea, and I could even sense a warning in his expression. A few years later, when we had to import again, I found that the Governement had change the duty rates and now both motors and generaters attracted 60%. That was my first brush with the law — something was arbitrary and unfair, but it could be changed. A few years later, our Company was raided by the Excise Department. I knew that my Company was small enough not to be liable for Excise Duty, and knowing the law allowed me to plead my case to my favour.

Nowadays, Law cannot be studied by correspondence. When my children were done with school, I starting thinking about studying law. PRAVAK was going full swing. 2010-2020 were very busy and productive years for us. Even though I wanted to pursue law I could not attend a college. Now that I am slowing down, partly aided by the Covid years, day to day operations are tapering; I am playing more mentorship roles and enaging in consulting work, all of which is being done online.

A few months ago, I discovered a law college nearby. Over the phone, the Admissions Counsellor was aghast that someone as old(?) >66years, wanted to seek admission and was adamant that I cannot join. I had filled an online form, and I was called by another person. I asked to speak to the Dean. She told me to come over to the College. Next day, at the reception, I said ” I have come for admission, and wish to meet the Dean”. The receptionist picked up the phone and said “A parent has come for admission”. I clarified that I was not the parent, but the student seeking admission. Eyes rolled; yet the damage had been done. The call to the Dean had gone through, and she asked me to come over to her office.

The Dean was a young person (like my daughter). She asked me why I wanted to study law. I told her that we were the first company to make robots and indigenize defence equipment . In this process, I learned that law pervades every aspect of human life. As a computer person I know that computers pervade every aspect of human life. I encountered many laws while running a company: taxes, import, disputes, contracts. I bought an apartment and there was a litigation, and I discovered the Real Estate Regulation Authority. I used the Right To Information Law. In this way, I learned how law pervades the entire fabric of society.

I also realized that law is very similar to computer science — laws follow the concept of classes, derived classes, syntax (rules), special cases, limits and validity. I started thinking about it from the point of view of the designer — who makes the laws. Just like we get bugs in software, because it is not possible to predict every case, similar is the case while making a new law. Fault tolerant systems design is very similar to drafting a good law.

Now that my children are married and settled, I would like to give back. I see injustice all around me. Food programs not reaching the hungry person. Education programs not reaching the child who needs to go to school. There is no one to help. The person can’t approach a lawyer because there are fees involved. I would like to be able to help without the need to make money from the service, and for that I needed to study law.

Our legal system says that I can fight my own case, but I can’t fight for someone else unless I am a lawyer. So to help, I must get certified. She seemed convinced, and granted me admission.

There is no age limit to practice law. Recently, a judge of the supreme court retired (yes, judges have a retirement age) and then started practicing as a lawyer again. So I could be an old lawyer and still help.

After my admission, as part of the uniform, I got a black coat, black pants, white shirts. I realized what a uniform means. It gets you access into courts, eventually.

A few decades back, literacy meant the three R’s, reading, (w)riting, and (a)rithmetic. To these was added computeRs. In today’s world, I am of the opinion that a basic study of Law should become a part of the literacy curicullum. Knowledge of Law and its application, both as a governing device, and a means to attain the objectives of social justice, equity and equality is extremely desirable. What do you say?

The Insurance Machine Model

As an electronics engineer working on control systems, I have had the opportunity to study a large number of physical processes, to develop models for their behaviour and to devise systems to control and/or to regulate them. I have always been interested in systems outside the domain of electronic / computerized control systems, and I have wanted to apply the techniques of modelling to other real life systems.

We have heard stories of warehouses catching fire, ships carrying cargo lost in storm, and how lucky the warehouse owner was because his warehouse was insured, or how unlucky the ship owner was because that particular ship was not insured. One of my friends headed an insurance company before retirement. During one of our chats he mentioned that insurance companies pay claims each year which were almost equal to the premium charged by them. I was surprised to learn that for government owned insurance companies, the claims paid were in excess of the premium earned.

How could a system take in less, and give out more, year after year, and why were so many privately owned insurance companies, whose motive is profit, entering the field of insurance, and thriving. This deserved some investigation and study. Something, on the face of it did not appear right.

The insurance business in India is regulated by the IRDAI (acronym for the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India). I happened to read some excerpts of their annual report in the media.

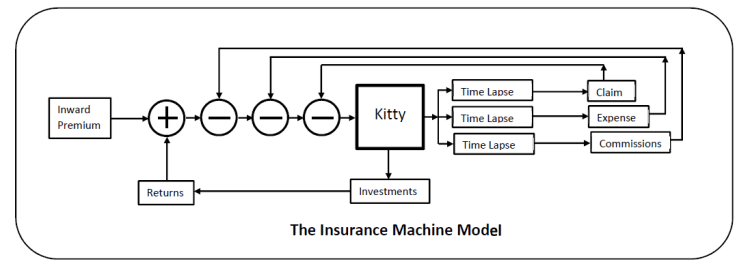

I downloaded a copy of the IRDAI annual report to understand the figures better. For the private insurance businesses, the claims were 80.5%, operating expenses 18.3%, and the commissions paid 7% of the total premium collected. This meant a loss of 5.8%. Yet, the companies made a profit which was nearly 6% of the premium earned, and paid dividend to its shareholders which was 10% of the capital employed. How do these numbers work out this way?

We are all familiar with insurance. Every member pays a premium for a particular period, and if any member makes a claim, then it is paid back from the funds collected. The assumption is that all the claims for money are genuine, including the reason and the amount.

How is the premium decided? I started with the most basic model. Let the total premium earned be P, the number of members be M, the probability of a member making a claim be p and the amount claimed be A.

For the insurance mechanism to work: P > (p*M*A)

This basic model does not account for the fact that the process of insurance needs to be administered. Insurance providers may take steps to reduce or mitigate the insurance claims, plus efforts to sell the insurance packages, usually done on a commission basis. There is evidence of an insurance company, which used to provide Fire Insurance , setting up its own Fire Fighting service to reduce the extent of damage. Other mitigating measures include programs to inculcate safe driving or diagnostic tests to detect diseases early. The Company would also like to make a profit. If the administrative cost was ‘a’ , the selling costs ‘s’, the commission costs as ‘c’ of the premium earned, the earlier equation for the relationship between premium P and other variables could be expressed as

P >= (p*M*A) + a*P + s*P +c*P + annual profit

It turns out that the IRDAI places limits on how much the administrative and operating cost can be, as well as the maximum commission that can be paid to generate the business. In a particular instance, taking the premium earned as 100%, the claims were 80.5%, administrative costs 18.3%, commissions 7.2%, and the company made a profit of 6%. Plugging the figures into the equation looks like

100 >= 80.5 + 18.3 + 7.2 + 6 i.e. 100 >= 112 …What? How? There must be an explanation.

The explanation is this: Companies collect premium in advance, and claims are paid later. This creates a fund surplus with the Insurance Company, which promptly invests these funds. The amounts collected by the Companies as premium are very large and even modest returns on them are sufficient to generate the additional 12% that they require to balance the above equation.

The Companies have special conditions which discourage members from filing a claim. If no claim is filed by a member, (s)he is allowed a discount in the subsequent year. This ensures that small claims which are less than the discount will not get filed at all. There is also a cap on the maximum amount that may be claimed in a given year.

In the annual report, the investments made by Insurance companies were more than 20 times their annual premium. In a particular year, the total capital employed by a section of the Insurance companies was 11000 Cr, which allowed them to generate annual premium collection of 91000 Cr, make an investment of 200000 Cr, an annual profit of 6000 Cr, and distribute dividend of 1000 Cr. No wonder there are so many companies entering the field of Insurance.

It appears as if the Insurance business is more of a Financial Investment Business whose byproduct is Insurance. The reason people put in their money into insurance policies is part logical and part emotional. The questions I will leave you with are: In what are ways are Insurance companies appealing to our emotions? Where does buying insurance make logical sense? What are improved methods of modeling the various probabilities and perhaps even alternate models of insurance that can provide comparable benefits at a lower cost?

How much wood would a woodchuck chuck, and other problems of estimation

I recently read a report in the newspaper. A company claimed to charge an Electric Vehicle in 15 minutes. Typical charging times are overnight or around eight hours. This was obviously a newsworthy claim, and it set me thinking. I know a thing or two about basic science and maths, and I asked myself the equivalent of the proverbial question “How much wood would a woodchuck chuck?”

I checked out that the batteries of today’s cars allow a journey of 400 – 500 km as a specification. I would take half of this figure to make the estimate. So how much energy is required to move a car with, let’s say, two passengers, a distance of 250 km in 4 hours. I know that my petrol-driven car gives me an average of 15 Km/litre on the highway and hence one would end up consuming 16.67 litres of petrol for the trip. If one computes the amount of energy in the 16.67 litres of petrol and accounts for the conversion efficiency, one would arrive at the energy used up during the trip.

The conversion efficiency could be determined by determining the energy losses, and subtracting them from the energy content of the fuel. The losses could be estimated by finding out how much fuel is consumed when the engine is merely idling. One could also estimate the losses in the heat of the exhaust, the heat lost in the engines through the radiator, the general heat loss through the body, the heat lost in the brake pads. Energy lost as the vehicle moves through the air (viscous losses) and friction losses in the moving parts. This is how my engineering brain buzzed.

A small voice in my head suggested a simple way of doing it. The published figures for the efficiency of a petrol engine is 30%. Also the calorific value of petrol is 47000 KJ/kg, and the density of petrol is 0.74.

Since one consumed 16.67 litres of petrol for a trip of 250 Km, it would allow us to estimate the energy used as = 16.67 * 0.74 * 47000 = 579510 KJ (Kilo Joules). Knowing the efficiency of the petrol engine to be 30%, the effective energy used for the trip would be = 0.30 * 579510 KJ = 173853 KJ. (This figure matches very well with the 318.2 Wh/Km of the MOBILE6 adjusted AC electricity consumption – Reference 1).

If the trip was undertaken by an electric car then after the trip was over, this much of energy would be needed to put back into the car battery, if the car was an electric car.

Hey, wait. The electric car is much more efficient that the petrol car. When the brake is applied in the electric car, the kinetic energy of the car is fed back to the battery and very little power is lost. It turns out that electric cars have an efficiency rating of 80 to 90%. So would the energy required to complete the trip still be 173,853 KJ? The answer after some thought was yes. The energy for the trip is still the same as it is the energy required to move a vehicle with passengers a distance of 250 Km, traveling at a speed of 60 Km/hour in a viscous fluid called air.

The time required for pumping 173853 KJ at the rate of 4 KJ/second (which is what 4 KW charger capacity represents) = 173853/4 = 43463 seconds or roughly 12 hours, 4 minutes. Typical car chargers deliver around 4 to 5 KW of charging power, and rarely are batteries fully discharged, which explains why it would take six to eight hours or an overnight charge to completely charge the battery.

On the other hand, if it was indeed required to charge the battery in say one hour, then the power required to be delivered by the charger = 173853/3600=48 KW.

Now that’s going to be a brute of a charger.

Multiple chargers of ratings of the order of 4 to 16 KW, working in parallel would be able to charge a car in a good fraction of the hour. This is where the current modern day Electric Vehicle charging systems seem to be headed.

I was able to estimate a claim that seemed outlandish to me at first glance with some basic pieces of information. There was a time when this information was available in textbooks and tables and only engineers and scientists might have copies of them on their bookshelves. Today this information is available at our fingertips on the internet. So with access to this information, and by practicing the techniques of estimation, a young person (or any person) may assess claims before investing their time and money into a technology. Similar techniques are also used to establish early feasibility of an idea.

In real life we may come across many statements where the full information is not provided. You can use estimation methods to determine the correctness of these statements with some degree of confidence. This is a scientific approach. With this story I hope to be able to pass on the technique of making estimates using incomplete input.

There are many formal courses where weighty terms like simulation, specifications gathering and other such abstract terms are used. They have a place in formal discourse, and my daughter, with all the training from her advanced degrees, loves to use them. I find them to be both too boring and too abstract to teach to any young apprentice. What I believe to be the central concept to teach is this: in addition to subject matter expertise, what goes into making a machine? With this central concept I return to my blog after a few months break. I hope to hear from those who read the blog about what caught their interest in current news, or what they might like to hear about next.

Bibliography:

- Tammy Thompson et al 2009 Environ. Res. Lett. 4 014002 Air Quality Impacts of using Overnight Electricity generation to charge plug-in hybrid electric vehicles for day time use.

Machines and Humans: Dumb, Smart, Intelligent, and More

“It’s just a dumb machine!” I’ve heard people say this. The contrast implicit in this statement is with the intelligence of a human. Sometimes this intelligence refers to cognitive capabilities such as abstraction, at other times it might refer to characteristics such as creativity or thoughtfulness or kindness.

Today dumb machines are often contrasted with smart machines which are further compared to intelligent machines. What makes a machine dumb, smart, or intelligent?

I think of the temperature controller in my electric iron. When electricity passes through a bimetallic strip and it reaches a certain temperature, the electric iron switches itself off. The bimetallic strip is a rectangle consisting of two different metallic strips laid one on top of the other and mechanically joined. Each of the two metals expands at a different rate with rising temperature. As a result, one strip grows slightly longer than the other. Since the two strips are bonded together, the longer strip must bend. The bend in the bimetallic strip causes the electric contact to break, and the iron turns off. Is the bimetallic strip intelligent? smart? dumb?

I think of another scenario. I imagine entering a room, picking up a remote control, pointing it to the air conditioner (AC), and pressing a button. Presto, the air conditioner turns on. I can adjust the temperature by pressing a few buttons Up or Down. The machine even shows me the temperature I have set. Is the air conditioner intelligent, or smart or dumb?

Now if I am able to enter a room and say “Hi AC, turn yourself on, and set the temperature at 25 degrees C” and the AC follows my command, is the AC intelligent, smart or dumb?

It does not end here. Let’s say someone else enters my room and says “Hi AC, turn yourself on, and set temperature at 25 degrees C”. The AC does not follow the command. This is because the AC realizes that the entrant is not an authorized person, because it does not recognize the face as a member of the household. Intelligent? Smart? Dumb?

Finally, I am asleep in my bed room. The AC is on, temperature at 25 degrees C. A hail storm is raging outside for several hours. The AC is monitoring my face temperature. As the outside temperature cools due to the hail storm, the AC slowly increases the temperature in minute steps 25.1, 25.2…..26.3 etc. I continue to sleep soundly. Now is the AC intelligent, smart or dumb?

My contention is that we need a consensus of what intelligence means in order to figure out how to implement intelligent behavior in machines. Alan Turing defined a test of intelligence in a machine as “the machine’s performance being indistinguishable from human behavior”. For an electric iron that turns itself off at a certain temperature, I am hard pressed to say that it will pass the Turing test. The air conditioner which responds to commands from the remote controller may be called less dumb, in other words, a smarter machine. If it recognizes my face and allows only authorized persons to change the temperature, then hmm, it has definitely done something which humans do, and is probably somewhat intelligent. If it exhibits a “care-giving” ability, and realizes that with the outside ambient cooling faster than normal, it would be advisable to raise the temperature setting a wee bit to ensure my comfort, it in all likelihood is exhibiting more intelligence.

As we strive for “human-like” abilities in machines, we will want to make machines that are creative, kind, thoughtful. The question I leave you to ponder is whether making machines human-like will end up showing us how good a machine human beings are?

How bright young entrepreneurs find the teachers they need

Intel brought out its first processor in 1971. I joined IIT Kharagpur to study Electronics in 1974. Over the next five years, I read and learnt all that I could about this new technology of making small computers. After completing my studies, I set about to make microprocessor based systems.

In the late 1970’s, the Indian Government did not allow just about any person to manufacture whatever they wanted to. They governed manufacturing with regulations and restrictions. The reason for these restrictions was that manufacturing required the use of both raw material and technology, some of which may need to be imported using precious foreign exchange. Other limited resources such as land, electricity and water were also regulated. Hence a license or permit was required from the Government to start a manufacturing unit.

I filed my application for setting up a unit for manufacturing microprocessor based systems. The concerned authorities informed me that the approval process was very lengthy and it would be advisable for a twenty two year old to start with a product that had been exclusively reserved for the small scale sector, and for which no permit or license was required.

I chose to manufacture automatic voltage correctors, or voltage stabilizers, as they were then known. During this time, the country’s electric power generation and distribution systems were unreliable. Electric power which should be supplied at 220V would fluctuate from 140V to 270V at different times. This fluctuation damaged high-priced luxury electric appliances, notably refrigerators, TV set, air conditioners and water coolers. This potential damage could be mitigated with the use of automatic voltage correctors.

I got hold of an existing voltage stabilizer and opened it up to see what it was made of. I could see a transformer, an electronic circuit which had been completely concealed, and a few relays. The only item which appeared difficult to me was the transformer.

I lived in Patna at that time, so I went to Calcutta, the nearest big city. I walked into the biggest shop in Calcutta that sold electronic components and enquired from the shopkeeper if he could help me make a transformer of my design. I sketched out a drawing of the product and the shopkeeper asked me to return in a week. A week later, I collected the transformer which was “slightly different” from what I had asked. I came home to Patna and made my own automatic voltage corrector which worked well.

After a few weeks, I returned to Calcutta and ordered four more transformers. He sought a time of three days. When I went to collect the transformers, they were not ready. The shopkeeper requested me to wait, and sent his assistant to bring the items. It was a long wait. I asked the shopkeeper to tell me where the transformers were being made so that I could go and collect them on my own. However, he was reluctant to reveal his source. The assistant returned without the transformers and I was asked to come back the next day.

I waited a day and went again. He sent his assistant to get the transformers and I noticed that the assistant came back within 2-3 minutes. I thought to myself, surely the person who is actually making the transformers is somewhere nearby.

The next time when I went to collect a new order, and while waiting for the assistant to fetch the same, I told the shopkeeper that I would smoke a cigarette outside, while waiting. I watched his assistant leave and I followed him. I saw him turn into the next building. The young entrepreneur in me did not have the courage to follow him inside so I returned. I collected the transformers this time too.

The next day I gathered my courage, returned to the market, and entered the building. On the second floor, I found an office with a small board saying “xyz transformers”. I walked in and met the owner. He turned out to be the supplier to the major manufacturers in the region. He told me many things about designing and making transformers.

This is when I learned that teachers come in all forms, from the professors who taught me electronics in IIT Kharagpur, to the self-taught geniuses making their living in a regulated yet competitive marketplace. And that I needed resourcefulness and luck to find them.

[Epilogue: Our automatic voltage correctors, called voltage stabilizers, sold continuously for the next 30 odd years. After about two years when the designs were well-tested, I gave the manufacturing reins to my younger brothers and moved to Delhi to ultimately start PRAVAK.]

Hot water as a service – the next killer app?

As I advance in age, the winter season gets harder on me. I wish for hot water to take my bath, warm water to wash my hands. I try to get the bathroom before my wife does, otherwise the water is not hot enough for my liking. On the really good days, I get to take my bath before the washing machine has been started. I cringe when I see the electricity bill.

This year I was thinking about what would be needed to make my life easier in the winters. Especially as I become older and crankier, this would make my wife’s life easier too. We hear the terms Internet of Things, Smart Devices, Private Transportation as a Service, etc. These were all rattling around in my brain when I thought about how the Electric Geyser could be a Service Provider. The service in this case would be to predict when we needed the water, at what temperature and how much. Of course we would want this delivered at minimum cost (small electricity bill). Finally at the end of the day, when there is no further demand for hot water, there should be as little hot water remaining in the geyser store as possible.

If the geyser must deliver the requisite amount of hot water at the desired temperature, on demand, it needs to learn the daily routine / usage pattern of the client(s). Three litres at 7 am, 80 litres between 8 and 9 am, five litres throughout the rest of the day, and two litres at 10 pm. There may be more than one client to serve, and each of the clients may have their own consumption patterns. In addition to the volume of water, the clients may have their own choices of temperatures at which they would like the water to be delivered.

The geyser must account for the time it takes to heat the water (we will assume that there will be no power cuts). It also computes the cost to keep the water hot when it is not being used by the client. Higher the temperature, greater the losses.

This description of the Geyser as a Hot Water Service Provider shares a lot of features with an optimization problem I had solved when I was young (but that’s another story for another day). The key aspect is to deliver a service under varying conditions to multiple users or clients while maintaining the quality of service and ensuring the least cost.

In the early 90’s such a system would have been unaffordable for a typical household. Advancements in the fields such as Sensors, Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things and Cloud computing have brought down the costs down, and today the necessary hardware and software pieces are not so hard to build.

Perhaps if I was twenty years younger I would have jumped at the possibility of bringing such a service to life. Today I wish for someone with technical skills and entrepreneurial passion to pick up the gauntlet. As for me, I will settle for the hot water.

A steam iron, a Fiat Padmini, and a flexible waveguide.

We were asked to do a project a few years ago. In a particular aircraft of the IAF, there was an equipment which generated high energy microwave pulses. The main equipment and its antenna were separated by 30 feet or so. The engineering constraints were such, that using a rigid rectangular “pipe” (also known as a waveguide) was not feasible, and so in a particular section of the “plumbing”, a flexible waveguide had been used. This flexible waveguide had broken. The equipment, imported at great cost, was rendered useless. The project was to fix it.

A waveguide transports RF energy (microwaves) from the source to the antenna from where it can be radiated into space. A broken waveguide meant that the equipment could not be used, and the aircraft for all its worth could not achieve its mission. It is not possible to show the actual flexible waveguide in this blog. You can get some idea from the picture below:

Many years back, when my wife and I were married, we got a Philips Steam Iron as a wedding gift. It was a beautiful iron, made in Holland, and we loved it. Sometime in the early nineties, when my children were still very young, my wife was using the steam iron, when the iron base and the handle separated, thus rendering the iron useless. Dismantling the iron revealed that two parts of a copper vessel used to heat the water had been originally soldered together, and had now come apart. I am an engineer, an electronics engineer, for whom using solder to join copper parts is part of daily life. One look at my wife’s face confirmed that this iron had to be fixed. I also knew that my own soldering iron was not up to this task.

Flashback to a few years before this. Our first car was a used Fiat Padmini car bought second hand from a serving government officer, who having been paid the agreed sum, let me drive away with it, but not before I caught the sad look in his eyes. The car served us well, till one day, when it was running very hot. I took it to a garage, and the car mechanic pronounced that the radiator was leaking. It was too expensive to get a new radiator for a very old car, and the mechanic suggested that the old one could be fixed. He agreed to let me watch him do the job. I saw that having identified the leaking joint, he proceeded to repair it by soldering with a huge soldering iron and a hot flame.

So when the iron broke, I went to the same mechanic, showed him the copper parts extracted from the steam iron and asked if he could solder them together. He was suspicious. He started asking, which car is this? it does not look like a car component? He wouldn’t do it. It took much coaxing to finally get him to join the two parts together. I gleefully took the parts home and put the steam iron back together.

This brings me back to the aircraft project. When the broken waveguide was handed over to us, I saw that it consisted of two copper parts. I had seen this before. This time, I did not wish to revisit the auto mechanic and go through his cross-questioning. So we made a contraption to hold the two components in place, and a heating arrangement that heated the parts to nearly 300 degrees Celsius. This re-melted the solder thereby causing the broken parts to be fused together. The repaired waveguide was fitted into the aircraft, which could now go up in the air, and spew out the microwaves, in a manner befitting its mission.

This blog entry reads like a story within a story within a story, like in Panchatantra and Mahabharata, which my grandchildren are reading now. The moral in this case, is to live all parts of life fully, and you will find those experiences influence technology indigenization in unexpected ways.

Indigenization by parts, and why the sum of the parts is greater than the whole

I was thinking about an apparent incongruity that I have encountered more than once in defense indigenization projects: we are tasked with replacing a part of a larger system, and because our replacement needs to fit into a legacy system, we often build digital circuits that mimic the behavior of much older circuitry, down to its idiosyncracies. This blog is about why such an apparent incongruity is actually the indication of a smart big picture plan.

The inventory of missiles needs to be tested at regular intervals to ensure that they will fire when needed. This is done by using a dedicated computer to provide test signals to the missile and verify its response. Each subsystem of the missile is tested right up to the point which says “Fire”. The final link is kept inactive so that the missile does not actually fire. This concludes the test, and the missile can be stowed away.

In the late fifties, dedicated computers for testing missiles were built using transistors, which was a more reliable technology then electronic valves. A small computer occupied half a truck. One such computer used a punched tape to store the control program. The tape would be loaded on an optical tape reader which was controlled by the computer. The contents of the tape were the control program to test the missiles.

After years of use, the tapes started degenerating and would get stuck in the reader, even breaking during operations. In the absence of the control programs, the missiles could not be tested. So the country might have had a stockpile of missiles, but it could not rely on them. The tapes and the readers were a very small but critical component of the entire system, and it became the point of failure that would have led the powers that be to dump the entire system and the stockpile.

The original equipment was several decades old, and the foreign supplier had discontinued the product a long time back. No spares were available. The only way to ensure that the missile stockpile remained useful was to indigenize the tape and its reader. Since the computer and other components were not to be changed, this meant replicating the original system exactly, in all its detail. In other words, inefficiencies or the design architecture in the older design had to be replicated, even if superior alternatives were available.

The indigenized substitute for the tapes and its reader costs let’s say $15,000. The missile testing computer that used the the programs on the tapes would be worth half a million dollars, but the cost of the missiles themselves would be in hundreds of millions, and their strategic importance – priceless.

The next weak link is the computer system itself, which is the logical next module to be replaced with an indigenous substitute. This incremental effort starting from parts and working through the system part by part is the most cost effective way to prolong the lives of strategic assets. Not only this, the expertise gained, and the ultimate impact of this expertise is worth much more.